The Doctors Company Foundation funds a reporting tool that empowers patients, families, and caregivers to communicate safety concerns with their care teams.

Grantee Profile

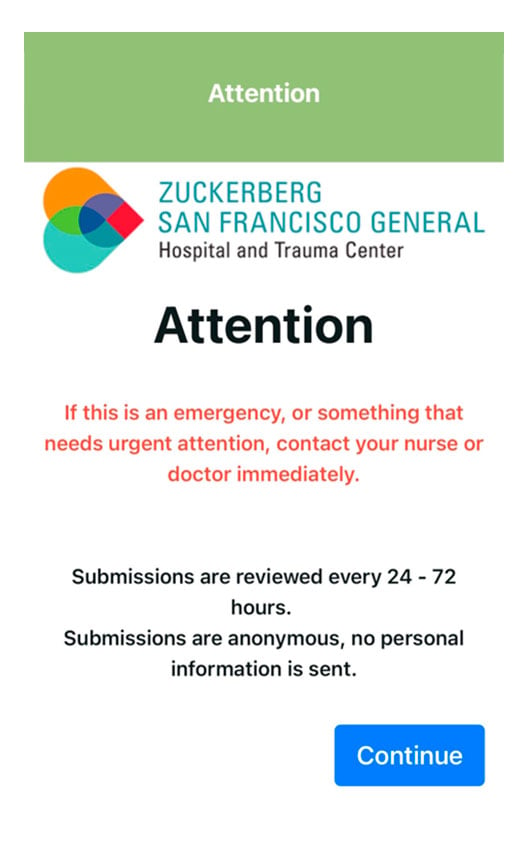

The University of California San Francisco (UCSF) is a large academic health sciences training institution in San Francisco, California. The study investigators represent the Department of Pediatrics, the Department of Family and Community Medicine, and the Institute for Health Policy Studies. UCSF clinicians provide care at the Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital, a large county hospital serving publicly insured patients from diverse racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds.

“Safe medical care is something we are all striving for, but many adverse events occur without being properly noted. The Family Input for Quality and Safety (FIQS) reporting tool allows patients and caregivers an easy way to share any safety concerns. I hope this tool helps patients feel more empowered to communicate, and also enables their care team to have a better understanding of patient experiences in the hospital.”–Anjara Sharma, MD, MAS, Associate Professor of Family and Community Medicine, UCSF

The Challenge

- Adverse safety events, including medication errors, misdiagnoses, and procedural errors, are a known and impactful cause of preventable morbidity and mortality. The costs of common in-hospital medical errors are immense. A 2008 study by Health Affairs estimated that the annual cost in the United States is $17 billion.

- Despite much investment and attention since the landmark report To Err Is Human, few gains have been made to reduce the burden of adverse safety events. Given the scope, scale, and impact of preventable medical harm, new ways to identify and resolve safety issues are sorely needed.

- Patient, family, and caregiver engagement in safety reporting is one promising avenue of innovation in patient safety. In-hospital safety reporting by staff is well known to under-report adverse events. Patients and their families or caregivers can observe unique adverse events missed by healthcare teams and report events at least as frequently as clinicians. “Patients and caregivers are often the closest observers of care,” noted Naomi Bardach, MD, MAS, Professor of Pediatrics and Health Policy. “Caregivers are at the bedside oftentimes for hours, and patients and caregivers only have one patient they are focusing on. They often have rich observations about safety that we can learn from.” However, many patient safety reporting programs rely on interviews or other more time-intensive means; efficient methods to gather patient feedback are needed.

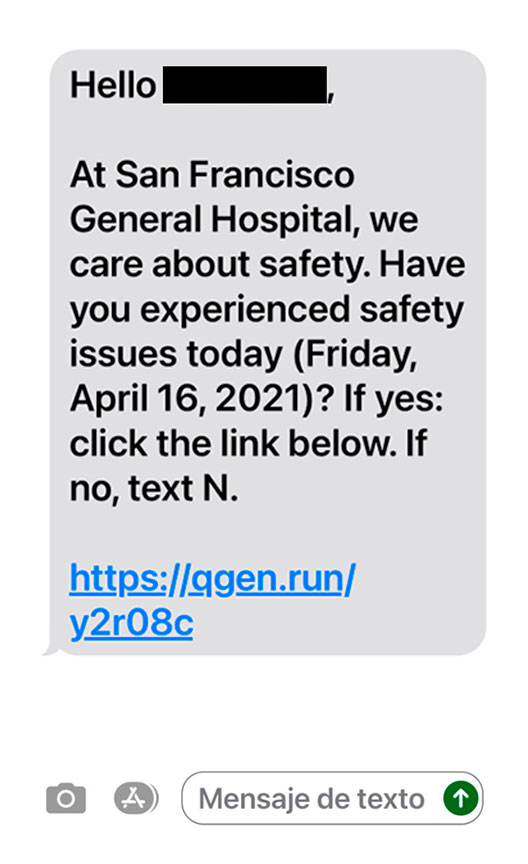

- Text messaging and mobile reporting is one potential strategy to engage patients and families/caregivers in safety reporting. Given racial/ethnic differences in adverse event rates,1,2 which are likely associated with structural and interpersonal racism and bias from healthcare providers, it is also imperative that such digital tools are accessible for a racially and ethnically diverse patient population so as to best track and address adverse events in an equitable manner.

- Among pediatric inpatients, the FIQS tool has demonstrated efficacy to identify adverse events not identified by staff in the organization’s internal incident reporting (IR) system. The tool has been implemented in several hospitals serving a pediatric population, with higher reporting rates for White patients and families compared to Latinx patients and families. We sought to adapt the pediatric-based mobile reporting tool for use with a racially and ethnically diverse adult inpatient population in a public hospital, for patients and families/caregivers speaking English and Spanish, and to assess its feasibility and usability.

- Of note: This study, funded by The Doctors Company Foundation, was a sister to a larger study for pediatric hospitalized patients across multiple hospitals in the San Francisco Bay Area leveraging a similar tool. In this project, the pediatric tool was adapted for adults.

Overview/Outcomes

Project Goals:

- Goal 1: Describe variations in safety events across care settings and populations using patient- and family/caregiver-generated safety reports and review reports in order to improve care. Using a real-time mobile phone tool, determine differences in report domain content by hospital setting, medical complexity, language, health technology literacy, and patient demographics. Hypothesis: FIQS reporting and content will differ by patient characteristics.

- Goal 2: Compare FIQS events to clinician-generated safety reports documented in incident reports. We use mixed methods, quantifying the number of overlapping and unique events from each source and using qualitative analysis to describe unique domains covered in each source. Hypothesis: Each source, including a portion of FIQS reports, will capture meaningful safety events, some unique and some overlapping, and will provide valuable safety information in specific domains.

Key Accomplishments:

- We successfully developed and implemented the FIQS tool in a safety-net hospital setting despite the co-occurring challenges of the COVID pandemic and subsequent staffing impacts on the study setting.

- We achieved enrollment of 75 adults and six caregivers for a total of 81 participants; these participants provided 65 reports. Participants were racially and ethnically diverse: Of patients, 56 percent were Latine/Latinx, 19 percent Black/African-American, 9 percent Asian/Pacific Islander, 8 percent White, and 3 percent multiracial, 5 percent were Other or declined to state. Of caregivers, four were Latinx/Latine, one was Asian/Pacific Islander, and one was White.

- Of the 65 gathered FIQS-entered reports from patients and families/caregivers, none were in the existing IR system. One was related (FIQS report noted a lack of repositioning in patient; a pressure ulcer was reported in the IR system).

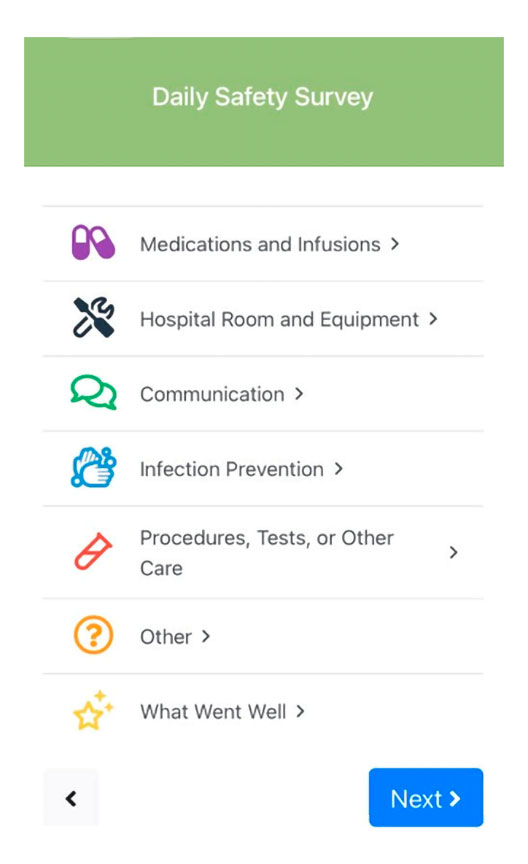

- Reports pertained to the following: medications (8 percent); hospital room and equipment (8 percent), communication (6 percent); procedures (8 percent); infection prevention (9 percent); other (27 percent); and “what went well,” a category for positive reports (34 percent).

- The reports were reviewed by unit and quality leadership as part of their safety improvement efforts.

Goals Achieved

- Our study found that in a racially and ethnically diverse adult inpatient population in a public hospital, a patient and family/caregiver-initiated reporting system is feasible and enables identification of adverse events that are NOT otherwise reported in existing safety systems.

- Our team achieved project goals through persistence, steady communication with our site leads, and flexibility to adapt in the setting of COVID and related staffing challenges.

Assessment/Takeaways/Next Steps

- Patients and families/caregivers can be informative partners in ensuring healthcare safety; patients and families/caregivers are experts in their own conditions and their own experiences and can report on safety-related observations.

- Improving communication about safety with patients and families/caregivers, through the means of an easy text-enabled reporting tool, is a feasible way to improve our understanding of safety issues in the inpatient setting.

A member of the research recruitment staff noted, “A lot of patients are interested and enthusiastic about participating. We encourage them to share their safety experiences, both positive and negative.”

For Further Information

- Anjana Sharma, MD, MAS, Associate Professor of Family and Community Medicine: sharma@ucsf.edu

- Naomi Bardach, MD, MAS, Professor of Pediatrics and Health Policy: bardach@ucsf.edu

References

- Stockwell DC, Landrigan CP, Toomey SL, et al. Racial, ethnic, and socioeconomic disparities in patient safety events for hospitalized children. Hosp Pediatr. 2019;9(1):1‐5.

- Khan A, Yin HS, Brach C, et al. Association between parent comfort with English and adverse events among hospitalized children. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(12):e203215.

We have included several examples of the text-enabled reporting tool below.

Example 1:

Example 2:

Example 3: